The Denial of Genocide is in and of itself Genocide

As I am writing, my chest tightens, barely giving room for an exploding heart of emotions ranging on a spectrum of rage, distress, and defeat. Despite spending the last few weeks giving interview after interview, answering questions and providing a synopsis of the IRS in laymen’s terms, it seems to fall on deaf ears. Those listening instruments attached to the genocide apologist, the one with selective hearing, the one who completely denies every truth - every body uncovered, every day since the first discovery at Kamloops Indian Residential School.

I will not mince words in this post. To be direct, the purpose of this piece is to introduce a paper I wrote in 2018 while in my second year of law school, for a class I was specifically asked by my professor, Amar Khoday, to take: International Criminal Justice. Our topics included crimes against humanity and genocide, for which he intended to focus on Indian Residential Schools. He wanted my input on the right way to go about providing the learning opportunity for others, and to participate in the class. Some may characterize this as an invitation to be tokenized, but I say this with the greatest respect for Amar, and with humility knowing that my contributions were valued by him.

“Thinking about this man and his parents this morning, and the 100,000’s of others who attended Indian residential schools across Canada for a century. In the 30 years we were together Joseph aban never really talked about his two years at Cecilia Jaffray here in Kenora. Then one day a friend visiting at our home asked him about his experience at the school. He said the thing he remembered most was being hungry. At 6 years old, he and his cousin would crawl out of bed at night, sneak out through the window and find their way in the dark down the hill to the root cellar. They would ‘steal’ turnips, make a fire, roast and eat the turnips, and then steal back to their beds. Loneliness and hunger stayed with him throughout his life. Not a scrap of food got wasted in our house. I used to get so frustrated when he would make the kids and then grandkids sit at the table and finish every spoonful on their plates.

Here he is on the steps of the school, six years old. His parents were also at CJ for a number of years, and got married soon after. Joe was sent to residential school when his mother got tuberculosis and had to go to the sanitarium in Thunder Bay.”

- My mom, Mary Alice Smith as she wrote on Orange Shirt Day 2020

My father was a Survivor of residential school, Cecilia Jeffrey IRS in Kenora, Ontario. My grandparents both went to St. Mary’s IRS in the same town. Imagine that - a small town in the heart of Lake of the Woods that opened not one, but two residential schools. He did not speak much of his experience, for reasons I can only speculate as he is no longer with us. Based on the little that he did share and the fact that he broke down in tears when the first apology by the Government of Canada was made in 2008, I imagine that it was a traumatic past to re-tell, one that carried shame and deep, deep hurt. I worked with IRS Survivors throughout 2011 and 2012, hundreds of them, who had to relive their trauma in an effort to seek compensation and justice for the horrific abuse they suffered. People often ask me what I was told. For obvious reasons of confidentiality, and for my own mental wellbeing, I would not and could not recount the details. My usual response, “Imagine the most inhumane thing you could subject a child to. And multiply the severity of that by a 100 times.” There are simply no words. And frankly, I am tired of having to parade our trauma in order for the world to finally believe.

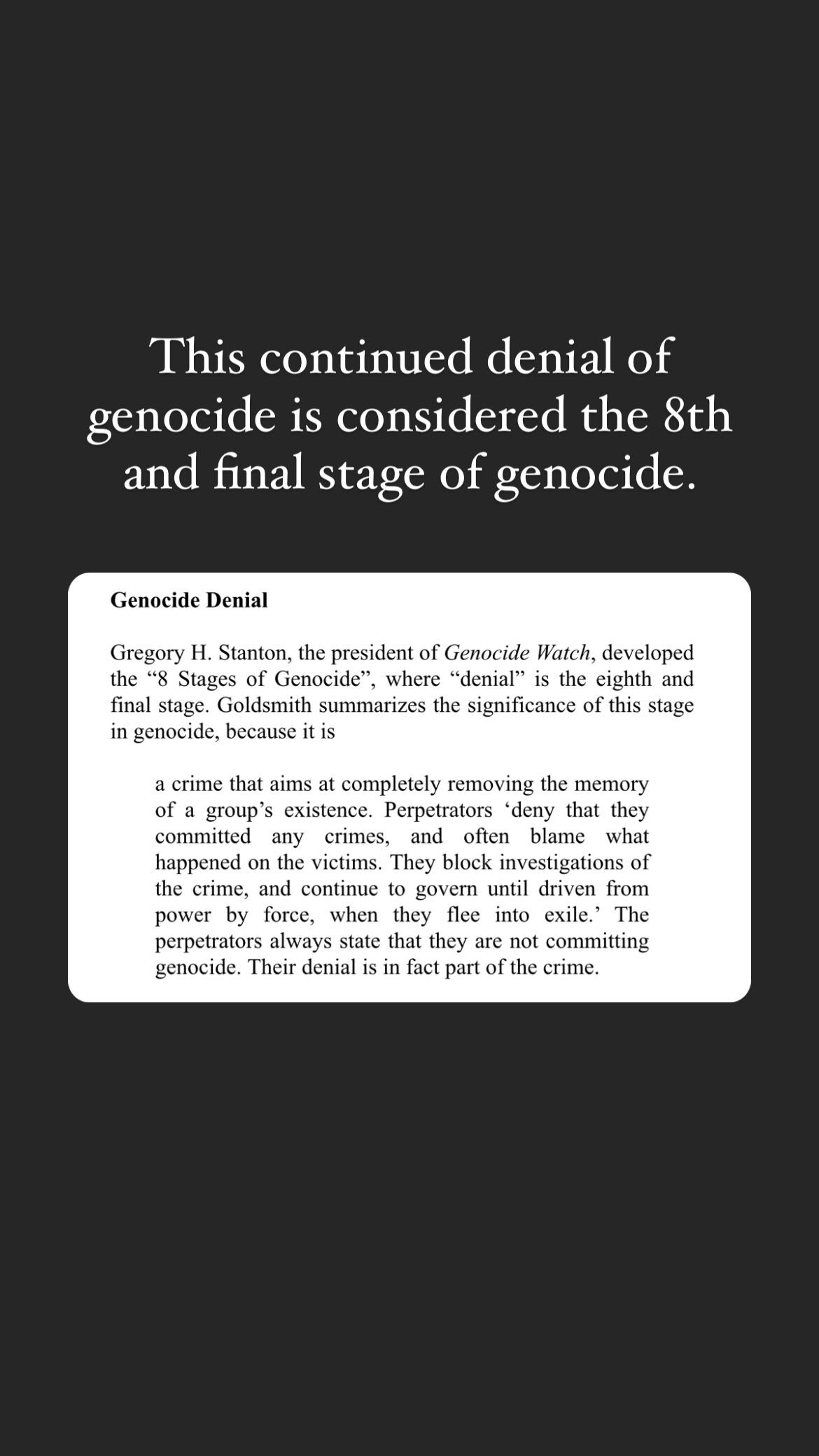

So I came to this class with a particularly heavy lived experience and knowledge. When we came to the subject of IRS as genocide, a quick scan of my classmates revealed, not surprisingly, that some did not feel it met the test of genocide. When I delivered my final paper at the end of the term, making the argument that the IRS was genocide, we did another scan. Every single classmate agreed that it was undeniably genocide.

This paper was a traumatic labour. I poured tears over literature written about my homelands, the plight and victories of Anishinaabeg, and found great pride and great sorrow - more so the former. I am grateful to live today as an Anishinaabekwe who was immersed in language and culture as a child. Who lived free from the grasp of assimilation tactics. Who was not scooped up by the ongoing systems of genocide - child welfare, MMIWG, the list goes on. My ancestors overcame so much in order for me to live a good life. I ran my fingers along photos of my father, my grandparents, my relatives, who all relived their stories to educate others in museum exhibitions such as Bakaan nake’ii ngii-izhi-gakinoo’amaagooomin / We Were Taught Differently: The Indian Residential School Experience, which I shared about in my first class presentation of my paper’s arguments. Stories that I listened to as a child at Survivor gatherings throughout Treaty #3 - Kenora, Sioux Lookout. Later, as an adult at the TRC gatherings in Saskatoon, sometimes hearing from Survivors who were only a few years older than me at the time, still in their twenties. It was a reminder that this was not a distant past - there were people from my generation that attended schools still running in the 1990s. It was a reminder of how different my life could have been if I was subjected to the same. That I may not be here today.

Of those who are still here today, many who live without homes and in poverty on the streets, society others them - unable to make the connection between the trauma of these systems and how it impacts our people still. We are so quick so honour the lives stolen, and yet, somehow it’s difficult to honour those who are still living.

Being in law school was a test of composure and holding on to these truths I had learned in life when my colleagues would defend the likes of Sir John A. MacDonald, who was infamous for his policies dictating the lives of Indigenous people. How anyone could defend a “leader” of such measure was beyond me:

“When the school is on the reserve the child lives with its parents, who are savages; he is surrounded by savages, and though he may learn to read and write his habits, and training and mode of thought are Indian. He is simply a savage who can read and write. It has been strongly pressed on myself, as the head of the Department, that the Indian children should be withdrawn as much as possible from the parental influence, and the only way to do that would be to put them in central training industrial schools where they will acquire the habits and modes of thought of white men.”

- Prime Minister Sir John A. Macdonald, Official report of the debates of the House of Commons of the Dominion of Canada, 9 May 1883, 1107–1108.

These were truths that almost every single one of my classmates had not learned in their own privileged educations. The “education” fed to lawyers and politicians of the past and the present. These were truths that every Indigenous law student has been forced to voice, in the face of denial and playing “devil’s advocate” for the sake of arguments. It was a complete attack on everything that I knew to be true, the very trauma that ran through my veins and informed my living values. And yet I had to walk the talk, and see my points through the systemic analysis that Canada’s system of law and standard of education demands.

It’s apparent that I wrote this paper with more than an ounce of bitterness. It is dry and void of any of my true emotions, a very pointed approach that I had to take in order to be taken seriously as a legal academic. It pains me that I could not write more on the ongoing truths that my family, my community, and all of our Nations continue to raise every day. I long for the day that these atrocities no longer define our every day conversations, but for now, it is completely and absolutely necessary that we continue to raise our voices. Whether that be through rage, through despair, through tears, there is no “right” way about it - no matter how, we must be louder than the voices that intend to deny our truths.

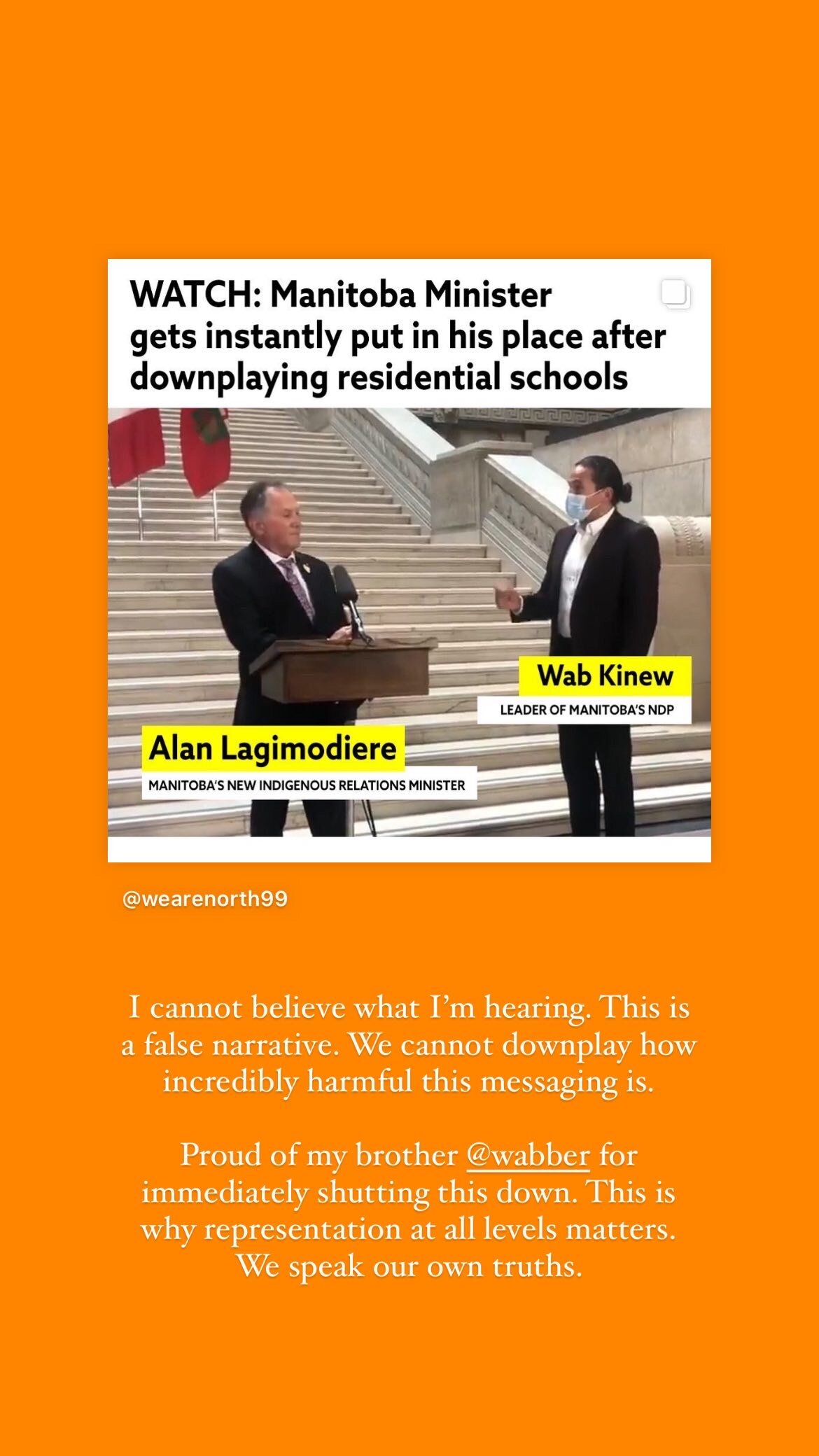

It is sad that it took a deeply upsetting event in Manitoba’s Legislature for me to finally share this truth. For years, I felt that my paper’s arguments were not good enough, not researched or backed up enough, that someone else would repute my points ten-fold and leave me embarrassed that I had not done the argument justice and I would somehow bring shame to my community. I realize now that there is no room for this shame - this is exactly the colonial intention of the attempted wiping out of our existence. I will never be afraid to speak the truth again. I will bring honour to the truth my ancestors survived and lived to tell of.

Click here to read my paper.

Below are photos from my Instagram post in lieu of statements made by MLA Alan Lagimodiere. I am grateful to those who shared my words and encouraged me to post the paper. I am grateful to my Treaty 3 brother Wab Kinew who, I’m sure through as much deep hurt as I felt, maintained composure and shut down a completely false narrative. I am grateful to my parents, my family, and my community, for seeing me through the success of law school, no matter how difficult it was, to give me the tools today to speak loudly with a clear, strong voice.

If you are in distress, the Indian Residential Schools Crisis Line is open 24-hours a day for Survivors of residential schools and their families. Please call 1-866-925-4419.